Powell’s Great Divide — The Repeat of 1929?

Introduction — The Paradox of Powell: Damned if he does - Damned if he doesn't!

I find myself struck by a glaring paradox in October 2025: inflation is finally tame (YES -it is!), unemployment is nudging higher – yet Fed Chair Jerome Powell keeps monetary policy in ultra-tight, hawkish mode. U.S. inflation has cooled to roughly 3% year-over-year (near the Fed’s target)[1], and labor market cracks are widening. Private employers shed 32,000 jobs in September according to ADP[2], and job openings have slipped to their lowest levels in years (about 7.2 million in August[3], down from the heights of 10+ million). Mass layoff announcements are back: Amazon is cutting 14,000 jobs, UPS 48,000, with tens of thousands more gone at Intel, Microsoft, and others[4]. In total, nearly 950,000 job cuts were announced from January to September[5]. Consumer confidence has soured – the Conference Board index just hit a five-month low as Americans report the toughest job prospects since early 2021[6][7]. By any traditional metric, these conditions would scream for Fed easing to support growth and employment.

Yet Powell stands firm. The Fed not only ceased its rate hikes only recently; it continues to signal “higher for longer”, clearly hesitant to cut rates despite the weakening data. Why? Because Powell faces a dilemma that echoes the late 1920s: a financial market bubble of the Fed’s own making. Years of near-zero interest rates and money-printing in the early 2020s have fueled massive asset bubbles – in stocks, crypto, real estate, even private credit. Now inflation is down and the economy is slowing, but Powell fears that cutting rates could reignite a speculative inferno in these frothy markets. He’s effectively trapped between the needs of Main Street and the risks on Wall Street. The result is a great divide: monetary policy that stays tight longer than the economy can perhaps bear, all because easing might further inflate what already look like historic asset bubbles. It’s a self-made trap – the Fed is afraid to pop the bubble it created, an uneasy parallel to 1929 when the central bank faced the same terrible choice.

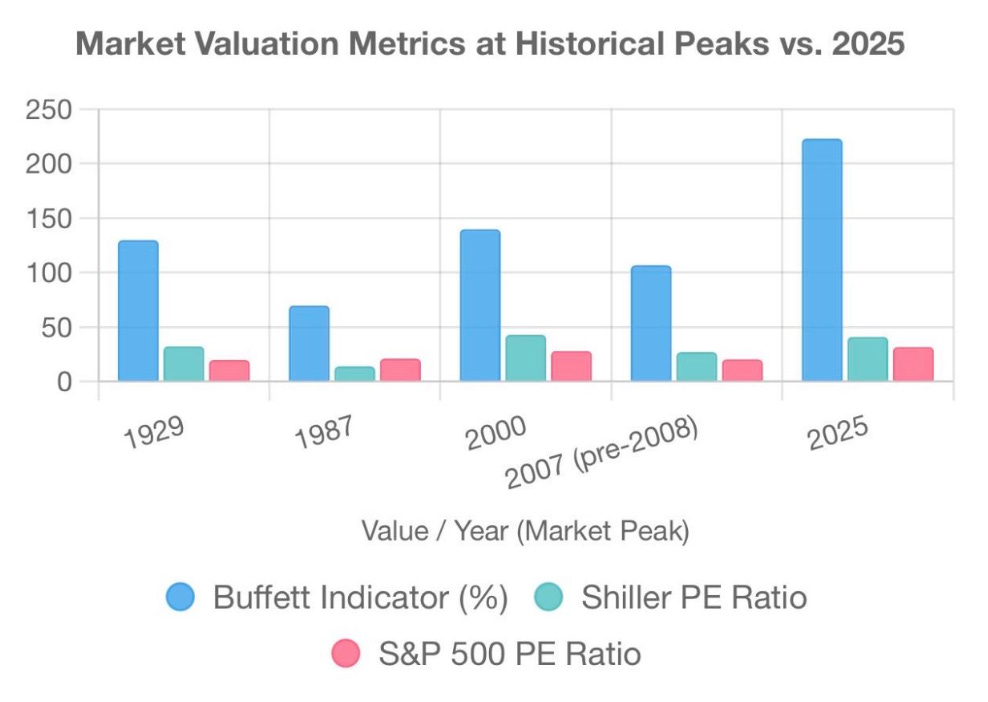

(Chart by @Great_Martis on X)

Market valuation metrics (e.g. total stock market capitalization-to-GDP and Shiller CAPE price/earnings ratio) at historical peaks vs. 2025, highlighting how extremes seen in 1929 and 2000 are being rivaled in today’s market.

My thesis is straightforward: the Federal Reserve’s post-pandemic easy money “monster” has grown into a market bubble so large that Powell now hesitates to slay it. In the late 1920s, the Fed tightened policy to contain rampant speculation – and ended up precipitating a collapse. In 2025, Powell risks repeating that fateful sequence. The Fed’s great divide between market objectives and economic realities could well become a repeat of 1929’s lesson in what happens when a central bank tries to tame a bubble without bursting it – and instead bursts the economy.

The Context — The Roaring 2020s Credit Boom

How did we get here? To understand Powell’s bind, I look back at the “Roaring 2020s”, a period uncannily parallel to the Roaring Twenties a century ago. In the wake of the 2020 pandemic, the Fed unleashed unprecedented easy money – zero interest rates, trillions in quantitative easing – igniting a speculative boom across nearly every asset class. Much like the 1920s (an era of cheap credit and technological revolution), the early 2020s saw an explosion of new-era optimism. Revolutionary technologies from artificial intelligence to blockchain and tokenization promised to reshape the world, and investors stampeded to get a piece of the future. Tech stocks soared to record highs; by 2025, seven mega-cap tech firms (the “Magnificent Seven”) made up over 30% of the S&P 500’s value[8], with Apple and Microsoft each exceeding \$4 trillion market caps and Nvidia astonishingly reaching \$5 trillion, larger than the GDP of any country except the U.S. and China[9]. This feverish AI-driven rally rivaled the late-1920s mania for radio and automobiles, when the Dow Jones surged sixfold between 1921 and 1929.

Easy credit didn’t just flow into stocks. Housing prices climbed relentlessly, with the low-rate era pushing real estate to valuations out of reach for many (recalling the Florida land boom of the 1920s). Cryptocurrencies and digital assets, despite a brutal bust in 2022, made a comeback – by 2025, Bitcoin and its peers were again emblematic of speculative excess, attracting waves of retail money. Perhaps most striking has been the rise of the private credit market – an opaque shadow banking sphere of direct lending. With banks constrained and yield-hungry investors abound, private debt funds ballooned almost tenfold, reaching over \$1.3 trillion in U.S. assets by 2024[10] (and ~$2 trillion globally). This private credit boom mirrors the late-1920s proliferation of investment trusts and broker’s loans that extended leverage to speculators. Today, even the instruments of lending have modernized: we see “buy-now-pay-later” consumer financing and even tokenized debt instruments on blockchain, slicing and dicing credit into new forms. Such innovations expand credit – but also blur regulatory oversight and create unknown points of fragility, just as unregulated margin lending did in the 1920s.